In honor of the 13th anniversary of our sons’ birth and passing, I decided to do something different this year. Rather than stumble through another annual rumination, I’m undertaking something significantly more ambitious: Interviewing 10 people I admire – all writers of extremely varied disciplines – and asking them for their perspectives on death and grief.

I’m not a sportsy guy, but I knew my friend Sam had a job that was related to sports journalism and that was about it. You can imagine my surprise when his name once came up in conversation and the person I was speaking with said, “Sam Miller? As in baseball writer Sam Miller? You know him? What’s he like?” And that was the moment I realized a couple of things: 1) Sam is a bigger deal than I thought and 2) Part of the reason Sam and I get along so well is I have no frame of reference whatsoever for what he does and, at least for Sam, that’s kind of a relief.

And even though he’s a legendary baseball journalist, author and podcaster, I have difficulty associating Sam with any of that. Sam is my smart, strange, funny, contrarian friend who seems to have an out-of-the-box hot take on every possible topic. I have no idea what death and grief have to do with baseball, but I knew Sam would have thoughts on the matter because Sam always has thoughts.

Jeremy: I tried coming up with a baseball-related access point to a discussion about death and grief, but I’m dry here. So maybe I’ll take the lazy path and put that back on you. You think a lot about baseball and I know you think about death. Do these topics overlap at all?

Sam: If you try to trace sports all the way back to their beginning, one place you end up is the gladiatorial games. In A Brief Theology Of Sport, Lincoln Harvey wrote:

Here the citizen—the citizen of a society where three out of five people died in their twenties—could learn how to die well. Of course, the gory nature of the killing would have appealed to the sadistic among the crowd. But the majority of the people were more interested in the dying than in the killing. Here they could witness true ‘manliness,’ the cardinal virtue of virtus again.

You know I’m a film guy and I’m not much for sports movies, as they usually hit me as manipulative and formulaic, but I’ll allow there are some great ones. One of my all time favorites is Oliver Stone’s Any Given Sunday, which is the best examination of what you’re talking about I’ve ever seen. (And Tarantino calls it one of the best films ever made, so I know I’m onto something.) But it makes the case that American football specifically is one of the closest things we have to simulating the life-or-death, gladiatorial mentality of Bronze Age combat-as-entertainment. We see the threat of death in front of us and it moves us.

I think a lot about what the central metaphor of sport is, and my position is that it’s about seeing the process of aging, exaggerated and sped up. In fact, I once wrote a long magazine piece about what specifically happens to players’ bodies as they age, and the whole time I worked on it I felt like I was writing to my therapist about my aging parents. We respond to baseball because we are moved by seeing a scaled-down version of the life cycle. Players quickly go through the phases of maturation, physical peak, then adaptation, then resignation, and eventually the end. The most touching phase is often the last, and every writer’s best pieces seem to be about athletes who are worse than they used to be. With very few exceptions, every player, from the humblest to the greatest, reaches a point where because of age or injury they are failing in front of us. This isn’t a small part of the experience. We try to ignore the knowledge that senescence and death are coming for us all, but our psyches must deal with these facts somehow.

That’s amazing. I knew you’d come through.

In terms of volume, you read more and write more than maybe anyone I know. What’s a book/article/piece of pop culture that’s influenced your thoughts on the nature of death? Do you have anything you can point to that’s made you think, “Ah! That’s interesting! Now we’re getting somewhere.”

This is a very literal answer—it’s not a work of art or of fiction but a self-helpish book about the actual nature of death, Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management For Mortals, by Oliver Burkeman. At least some of my death anxiety comes from the thought that death = lost opportunity. Once I die (and/or as I age), I can no longer do all the things. The way we armor ourselves against this is by trying to do all the things now, as though we’re making progress toward a fulfillment goal. But Burkeman makes the case that this is absurd; that if you try to, for instance, read all the important books—which is definitely a goal I had for a long time, and that I see now was a reflection of death anxiety—you will read maybe 1/1000th of all the worthwhile books there are, and none of the worthwhile books that are going to be published in the future. Other people do this with travel, or career goals, or fitness—but the most extreme traveler will not see more than 1/1000th of this world (let alone the cosmos), etc etc etc. Resisting these truths simply reinforces death anxiety, by constantly reminding us of how little progress we are making or could ever make.

It’s much better to accept the finitude of life, which applies not just to what we experience (the books we won’t read) but to what we are. Each of us mostly already barely exists. We don’t exist in most places on Earth right now; we don’t exist to most people on Earth right now; and we don’t witness or experience most of what’s happening on Earth right now. So when we die to this Earth, in a numerical sense it will actually change very little. I find this freeing. When I get anxious—and I consider all anxiety to be at least partially death anxiety—my mantra is: “Think about all the places you already aren’t.”

Sold. Four Thousand Weeks = now on my Kindle.

I hard-relate to the idea that death is the deadline of the project of building a meaningful life of exploring, creating, building and experiencing. I’m in the midst of a creative project with another artist right now and I recently told them, “I’ve wanted to ask you to do this for years and I’ve always talked myself out of it. I regret that I waited until I was in the latter half of my 40s to ask.” And they essentially said, “Well, the important thing is we’re doing it now, so put your pants on and let’s go.” And it 100% comes down to the march of death coming for me. I’m looking at the clock and thinking, ‘I’m over halfway done. And I’ve done maybe 25%? 30% of the stuff I’d hoped to do at this point?’ It’s a low-burn panic that hangs onto the back of my neck each day.

How much do you think about the afterlife? What aspect of it doesn’t get enough discussion?

I don’t think much about the afterlife. I have a fairly immature/inexperienced relationship to death and grieving, and my death thoughts are definitely more focused on a) fear of the actual pain of dying, i.e. there is a very good chance the the most painful moments of my life are going to be the last thing I experience, and as a fairly committed avoider of pain I think that sucks; b) the fear of losing Earth, all the sensations and ambitions of my Earthly life. Like anybody I sometimes speculate on what the afterlife could be, how it could fit into the meaning of this all. But mostly I just trust that it won’t be cruel. Nothing about my experience with God leads me to worry it will be cruel.

In another conversation in this series, a friend who works with a lot of dynamic, high-performance people mentioned that she’s noticed that a common trait among them is they spend minimal time thinking about death and are much more rooted in the present. So you’re in good company in not ruminating much on the Great Beyond.

The moment of death, however, is something I think a lot of us think about but rarely talk about. In fact, I’ve noticed that older people in my life (and some who have passed away), sometimes appear to talk about death less as it gets closer. There are definitely exceptions to that, but there appears to be a point in life where many/most people tend to close up about it because the reality of it is so immediate that there aren’t really words anymore. And I’ve wondered if that’s an apprehension or fear about the moment of death itself.

But I agree with you that whatever’s next won’t be cruel. While I’m a person of faith, I don’t believe in Hell – or at least Hell in the traditional “hot-place-of-torture-for-doing-or-believing-the-wrong-thing” sense.

When you and I get together, we usually talk about movies and the experience of being dads. What, if anything, has fatherhood done to change or evolve your perspective on death?

There was a point when my daughter was maybe 7 or 8 (or maybe 4 or maybe 11, I don’t remember it precisely) that I realized, “oh, she definitely knows me now, I’m permanent in her brain.” I very consciously realized at that point that I was much less resistant to dying than I had been before. I don’t want to die. But I’m clearly in physical decline, I’m probably in creative decline, my parents got to see me become a happy adult, I’ve had a marriage that has reprogrammed my brain into something less egotistical and alone, I’ve made some lives better, and I’ve experienced enough of the world that I’m almost literally never surprised by how anything feels, tastes, looks, etc. anymore. So when I realized that my daughter understood me and would remember me forever, I concluded that my life was basically complete. I had reached a point where I couldn’t, or wouldn’t, see my death as “tragically young” anymore.

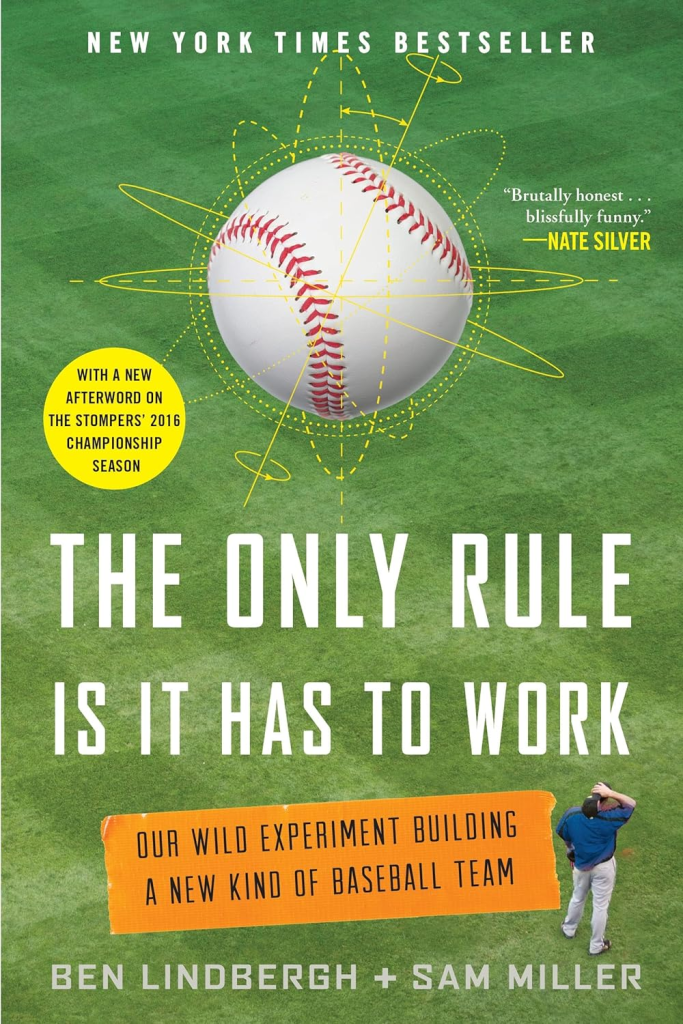

Sam’s voice—particularly as it relates to all things baseball—can be found all over the place. From televised interviews to podcasts to articles to blogs to books.

One book, which he co-authored with collaborator Ben Lindbergh, is The Only Rule Is It Has to Work: Our Wild Experiment Building a New Kind of Baseball Team. It chronicles the story of an independent minor-league team in California, the Sonoma Stompers, who offered who offered Sam and Ben the chance to run its baseball operations according to the most advanced statistics.